Sometimes the size and power of a grassroots social or political movement is too vast and too varied for us to be able to truly ‘see it’ …or to understand it’s impacts. It’s only as we look back and unpick the different elements, actions, actors and allies that combined to create such an organic, evolving movement for change that we start to see where its power really came from.

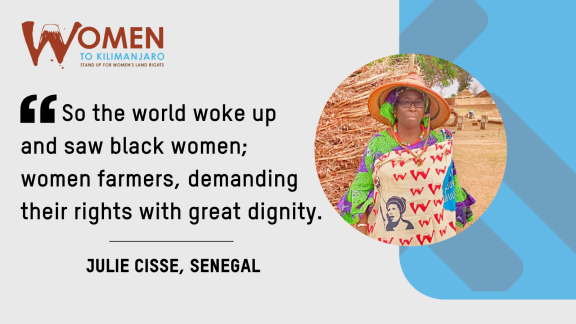

As the African Kilimanjaro Initiative of Women Farmers Forum (AKIWOFF) prepares to celebrates 10 years since the Women to Kilimanjaro campaign launch, eight activists look back at the significance of their collective actions then and now, and what these mean for women’s land rights organising and food security, food sovereignty movements today.

***

In 2016 nearly 600 women farmers from across the African Continent marched to the base of Tanzania’s Mount Kilimanjaro to demand their equal rights to land. 60 of the women – each of them farmers and food producers from rural communities across Africa – went on to summit the continent’s highest mountain.

The press loved them. The media coverage and the women’s sharp campaign slogans made visible a previously-invisible issue; one that caught imaginations and mobilised popular interest and support across the continent. Here were hundreds of well-organised women farmers - representing millions more - coming together across boundaries of distance, language, ethnicity and religion to demand the one same thing: their right to own the land they farm.

As we prepare to celebrate the campaign’s 10th anniversary, we see the impact of the ‘Women to Kilimanjaro’ campaign firmly embedded in agricultural laws, protections, policies and practices across Africa.

“For example, in local communities, they always have what they call their Councils when it comes to land issues and other decision making. Before, it was made up of men but now they have created a space with the help of the campaign and it’s a must for them, those men, to include women.”

In the 10 years, African Union Member States have reviewed and strengthened women’s land ownership in national land policy. In our interviews with just eight of the over 500 women that took part in the campaign we document more than 15 land policy and governance changes linked to the Kilimanjaro women farmers: From a Presidential decree in Zambia allocating 50% of government land to women; to the introduction of seven different financial support programmes for women farmers in Senegal; to the mandated participation of Cameroonian women in local Parliaments and Malawian women in Land Distribution Committees; to protections for Ugandan widows securing land rights guarantees and support from her family in her terms. Together, these measures - and countless more - provide an astonishing array of perception of legal protections and concrete benefits for women and for women farmers and widows in particular.

“Through our campaign, rural women have engaged and contributed a lot in reviewing and strengthening these policies…not only in Malawi but in most of the countries where we’re active, the policies have been reviewed.”

Across the continent, the policy and legal changes initiated by the Kilimanjaro women have contributed to what is, in many places, a mass transfer of state and customary[i] land to women farmers and their associations. The women’s vocal demands have mobilised political will and helped to unlocked state and private sector financing and technical support.

Critically too, rural women were finally being recognised as sector experts, capable advisors, and serious allies in the debates and decisions surrounding land and agricultural policy. These were farmers with practical, proven, home-grown solutions to the interconnected challenges at the heart of Africa’s food production, land management, economic and environmental security and wellbeing.

‘And this influence was happening at the Continental level too, where AKIWOFF has also been attending a lot of meetings and conferences at the AU. I was part of some of them. For example we attended the agricultural meetings in Tanzania where we even met the former Head of State talking on developing our own food systems. At that level AKIWOFF is well known and given an advocacy platform – even being part of the Malabo processes.[i] There were about 15 or so members of AKIWOFF there. We talked about land issues, gender too…for women to be equal partners; to be in the policy processes. And about our foods; the right to food. I remember some of the contributions that were made and that we were advocating for being captured in the final documents from the things that poured out from us.’ Grace Tepula, Zambia

In 2017 the AU integrated all 15 of the women’s original Charter of Demands into its Land Policy Guidelines. The significance of this previously unimaginable achievement – catalysed entirely by Africa’s most invisible citizens - cannot be overstated.

Many challenges remain. For example, there are inconsistencies in the way women’s land rights laws and policies are implemented in Africa. Many of the women sharing their campaign stories called for the introduction of binding measures and more forceful accountability mechanisms to help close the implementation gap – particularly in Member States where government and customary law are still not fully aligned.

“We hear of countries that have not changed. As AKIWOFF, we should put a collective focus on those countries/communities.”

They shared concerns too about the support still needed from governments to women farmers responding to the interconnected political, environmental and market pressures of commercial farming, climate crises, and protracted conflicts that keep women out of their farms.

Finally, the women whose stories are collected here, also called for continued funding for locally-led programmes of women’s land rights education, engagement and awareness raising; particularly for those targeting traditional leaders in areas where women’s right to own land remains a taboo.

Their expert advice must be at the heart of our Action Plans for the next 10 years of collaborations to promote women’s rights to land. But first, as we mark this significant 10th anniversary we must noisily celebrate the depth, breadth and mountainous scale of the Kilimanjaro women’s achievements – and the strong policy and social change foundations that they have gifted to future generations!

[i] Customary land is land that is administered according to long-established codes of community customary - or ‘traditional’ - law.

[i] The 2014 Malabo Declaration built on the 2003 Maputo Declaration under which AU Member States committed to spending at least 10% of their national budgets on agriculture. The Kampala Declaration takes this further yet, outlining a 10 year strategy and action plan to transform Africa's agri-food systems and ensure food security.